Systems Analysis of a Concepts Director

Abstract

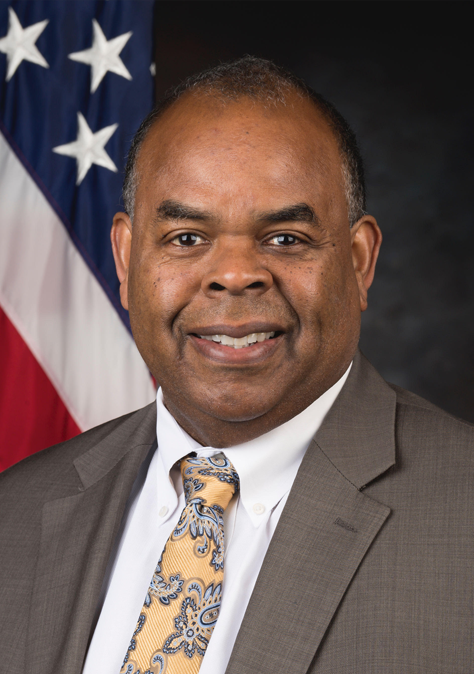

Melvin Ferebee started his NASA career as an intern while still in high school. Over the course of his time at NASA, he has grown as an engineer as the technological capabilities of the agency have grown. From plotting wind tunnel data by hand and running tours for public affairs to serving as a project manager for the Ares I-X rocket and sitting on console at Mission Control, Ferebee’s career has spanned many aspects of aerospace engineering. Now, as he wraps up his career at the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, VA, as the Director for the Systems Analysis and Concepts Directorate (SACD), Ferebee shares his experiences as a NASA employee and the lessons he has learned along the way.

Background

Growing up watching Walter Cronkite and Astronaut Wally Schirra cover NASA launches during the Gemini program, Melvin Ferebee decided by age six that he wanted to work at NASA. If being an astronaut didn’t work out, he supposed that being a rocket scientist or working in mission control would also be acceptable options. As a high school senior, Ferebee, a native of Norfolk, Virginia, was accepted to a NASA internship at the Langley Research Center. Packing up for his first day, he quickly realized this was much closer than where he thought he was heading—the Kennedy Space Center in Florida!

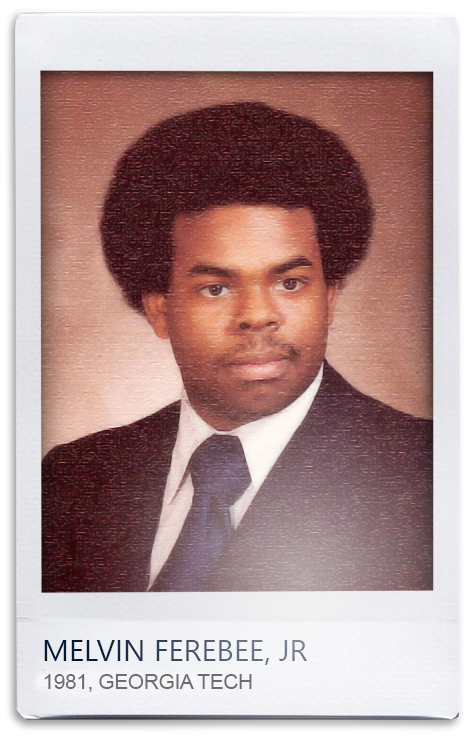

Although Ferebee’s parents were not of means, they were fully supportive of Ferebee’s career goals, saving up to send him where he needed to go. After completing his internship and discovering that the next best step to a NASA career was to join the co-op program, Ferebee had the assistance of the Langley Deputy Director to present the idea to his father. With that endorsement and the realization that his son could earn a degree at Georgia Tech as a co-op student for less than it would cost to go to Virginia Tech as a full-time student, he was convinced. Ferebee quickly signed up for summer term classes, which started just a few days after his high school graduation, to be eligible for a fall co-op rotation at Langley.

“You treat [a challenge] as another problem and you figure out ways to solve the problem.”

In addition to financial concerns, Ferebee also dealt with societal pressures. “[I was] a Black kid, and the Black kids in my [Norfolk, VA] neighborhood only went to local schools. [I was] going to Georgia Tech. Dad said, ‘You stay there. Don’t come back to the local schools having failed.’ [It] felt like I had the weight of the locality on my shoulders. I was a hermit, I didn’t party. It was fear that motivated me. I couldn’t disappoint and embarrass my parents. I needed to do what I needed to do in order to come home with a degree.”

That dedication to his studies and co-op rotation work paid off. After successfully completing his bachelor’s in aerospace engineering and eight co-op rotations, Melvin Ferebee became a full-time engineer at NASA Langley.

Methods

As a high school student, Ferebee started his NASA career off strong by interning with “Hidden Figure” Dr. Christine Darden. She taught him to plot lift-over-drag (L/D) curves from wind tunnel tests and to fit curves to that data, all by hand. Even though Ferebee didn’t understand all the math at the time, he learned about the different airfoils and how the data was generated in the tests. Doing all this work on paper was tedious, so when Ferebee found out that there were actual electronic computers drawing those same L/D curves for the space shuttle outer mold line, he became more excited about making those computers do the repetitive tasks for him.

After finishing his first term of classes at Georgia Tech, Ferebee was assigned to Public Affairs as a tour guide. While conducting hundreds of tours through a sample house showcasing how NASA spinoff technologies were utilized in everyday life, he wondered, “Is this what I’m going to do for the rest of my career?” Fortunately for the aerospace engineering student, other co-op rotations involved testing in the wind tunnels, analyzing lightning arresting for fighter jets, and learning “newfangled” computer techniques to automate data analysis with the Systems and Experiments Branch. This last position so enthralled Ferebee that he returned there for his remaining co-op sessions, which eventually allowed him to be hired full-time after his college graduation.

Ferebee spent the next twenty years of his career with this group, which was reorganized and renamed the Space Mission Analysis Branch (SMAB) and placed within SACD. With a goal of becoming a Branch Head, and eventually a Director, he kept learning, earning his master’s in mathematics from William and Mary.

For Ferebee, one highlight as a SMAB engineer was participating in the LIDAR In-space Technology Experiment. This was this first time that the Agency flew a laser to look at clouds and the atmosphere. As part of the team that planned the various data takes, Ferebee had a seat on console at Mission Control. During the experiment, a volcano erupted, so the data coming down was of extra interest to see how the clouds were impacted by the event. While that was going on, a glitch occurred in the data recording system, so Ferebee’s team quickly worked out a new plan in real time to use alternate telemetry assets to acquire the data, ensuring a successful experiment.

“Every person who leaves SACD is a person who takes systems thinking to be infused somewhere outside the directorate, effecting change throughout the center and the Agency.”

After achieving his first goal of becoming Branch Head, Ferebee kept working to develop the necessary skills for a Director position. Part of that process involved going through the Senior Executive Service (SES) Candidate Development Program, which involved a year-long detail outside of NASA. Ferebee spent this time in Washington , D.C., as a staff member of a Virginia congressman. He used his engineering management skills to improve the office operations, leading to higher personnel morale. He also ran Town Hall meetings, Congressional Black Caucus meetings, and involved think tanks from both liberal and conservative perspectives. As an objective, data-driven engineer, Ferebee said, “No one could tell what [political party] I was—I’m a rocket scientist!”

Returning to NASA, Ferebee left SACD to explore program management and flight projects. After holding positions in strategic planning and as a technical liaison for the Space Shuttle program, he joined the Ares I-X Integrated Design and Analysis team as the Project Manager. As this was the first rocket built and launched by the US government since the Saturn V, being invited to watch the launch in person was another career highlight for Ferebee.

Landing a six-month detail as the SACD Deputy Director confirmed for Ferebee that a Director position would be a dream job. However, when the Langley Associate Director asked if he would serve as the Director of Equal Opportunity Programs, that was not exactly what Ferebee had in mind. Wondering why he was asked and if the move away from technical work would be worthwhile, he was reassured by the Center Director, “You have a way with people that no one else does. This [position] gives you the chance to sit at the table with all the other Directors and have a say in what the center does.” After thinking it over for fifteen minutes, Ferebee accepted the job.

Discussion

With years of varied experiences at NASA, Ferebee has learned many lessons that still apply today. One key aspect was how to respond to challenges, including those based on his identity. While he was a co-op student, Ferebee entered a conference room with his projector slides to prepare for a presentation. Another man got up and handed him the trash can. “I am one hundred percent sure that he thought I was the janitor.” Although the man apologized afterwards, that incident has stayed with Ferebee his whole career. “It was more of a fire lit under my butt. You’re not going to diminish me.”

“Everything else was just day-to-day as a systems engineer. You treat [a challenge] as another problem and you figure out ways to solve the problem.” As Branch Head, Ferebee led the first Independent Program Assessment for the proposed 2001 Mars Orbiter and Lander missions. The program didn’t think they needed an independent assessment, so there was much resistance to integrating the assessment team with the mission team. To stave off the view that the Langley team was hindering the project, Ferebee included assessors from every center. This intra-Agency team concluded that the lander mission was not viable, eventually leading to its cancellation. Although the assessment did not return positive results for this particular mission, the task led to the permanent creation of a team for independent mission proposal evaluations.

One challenge Ferebee faced ended in failure. He wanted to create a systems analysis consortium across the entire Agency so that as Headquarters posed a question, it could be sent out and assigned to the relevant center organizations. The consortium started out successfully but collapsed due to intercenter politics. Ferebee took this hard, but he learned that he personally could not hold the organization together. The Center Director also advised him that more coordination at the Center Director level was needed and that he should reach out to leadership, as with the help of people in more influential positions, different results could, perhaps, have been obtained.

“I might not have been the best on the programmatics, but I was pretty good with people. If people are happy, the work will get done.”

Ferebee’s experience leading and working with people has also taught him several lessons. “I might not have been the best on the programmatics, but I was pretty good with people. If people are happy, the work will get done.” One example of putting this into practice occurred shortly after he became Branch Head. The NASA Administrator offered up several million dollars to develop revolutionary aerospace concepts that covered science, human exploration, and aeronautics. This allowed several SMAB analysts to go off and work on projects they really liked, such as a human mission to Callisto or prepositioning propellant depots to enable future exploration missions. The funding also allowed for the creation of the Revolutionary Aerospace Systems Concepts project and its spinoff, an annual university design competition, that involves many passionate SMAB members as organizers and judges.

As Branch Head and later on as SACD Director, Ferebee understood the importance of systems analysis to the whole agency. “With SMAB, it’s in our DNA to interact with our customers.” Oftentimes, these customers can include leadership such as Project Managers and Associate Administrators at NASA Headquarters. Growing that experience for SACD employees working with these high-level customers and learning to communicate effectively for that audience was a priority for Ferebee. As the directorate has grown, Ferebee has continued to encourage people to take opportunities outside SACD. He sees this employee movement as one of his biggest accomplishments as SACD Director because “every person who leaves SACD is a person who takes systems thinking to be infused somewhere outside the directorate, effecting change throughout the center and the Agency.”

How have these experiences influenced how Ferebee saw himself at NASA? “I didn’t know what kind of power I had. Within the last fifteen years or so, I realized that you need to speak the power. If something isn’t right, say so.” This conviction has allowed him to impact workforce diversity growth efforts; after championing that cause, he felt he could call out other inequities. Ferebee is now known as the person who will start the messy conversations to address group accountability and sensitive issues. “I don’t think [these conversations] would have been had if I hadn’t been there to force the issue, and not just because I was the Black guy.”

Conclusion

As he retires from his full career at NASA, Ferebee provided some words of wisdom for current and aspirational NASA employees. Obtaining technical competence and associated communication skills should be an initial goal early in a career, and new employees should aim to infuse their fresh perspectives and new techniques with current operations. The branch is the first level of technical competence and that level is needed to lead. Taking those systems analysis skills elsewhere and gaining programmatic or flight project experience is also suggested. “NASA likes people with diverse experiences, so even though SMAB provides some of that because you work with people outside the organization at other centers and Headquarters, by all means, get out! You can always come back.”

For those looking to learn as a mentee, “soak up everything folks tell you. …As a mentor, I am here to help, and I will guide you, but I won’t do the work for you. You’re smart, you’re here to do this work, you’re here to learn. I will point you in the right direction. It is up to you to proceed. …[However,] as much as I am mentoring you all, you are mentoring me to inform me of the things I need to be aware of and understand.”

“For leadership, it’s good to be technically competent, tactful, and political. Just remember that you are not the smartest person in the room; it’s the people supporting you that make you the smartest, so you don’t have to say everything… Pass off the questions you can to give others the opportunity to share and get face time.”

Ferebee had several excellent mentors that possessed these characteristics. One, “Hidden Figure” Katherine Johnson, asserted, “You are no better than anyone else, and no one is better than you.” That level of humility has stayed with Ferebee for his entire career, and he wants to provide that same type of mentoring support for the next generation. “My career is over, yours is just starting. You do the work, I’ll be there to back you up.” With this mindset, it should be no surprise that Melvin Ferebee leaves a legacy of technical excellence and supportive workplace culture in SACD and beyond.

Acknowledgments

The people of SACD would like to thank Melvin Ferebee for his service as our Director.

Author/Contact: Emily Judd

Published: April 2021