Little RASC-ALs Prospecting for Big Ideas, featuring Chris Jones and Shelley Spears

When you have a big question you want to answer, collaborating to generate new ideas can be helpful. That’s the idea behind the Revolutionary Aerospace Systems Concepts Academic Linkage (RASC-AL) challenges, sponsored by NASA. The suite of competitions under the RASC-AL umbrella “consists of premier university engineering design challenges aimed at informing NASA’s approaches for future human space exploration.” These challenges give university students a real-life space exploration problem to investigate, plan, and analyze at differing stages of development.

The Space Mission Analysis Branch (SMAB) at the NASA Langley Research Center has been a longtime sponsor of the RASC-AL competitions. To celebrate Langley’s centennial anniversary in 2017, NASA decided to conduct a special edition RASC-AL competition: the Mars Ice Challenge, which in subsequent years evolved into the Moon and Mars Ice and Prospecting Challenge (MMIP). One crucial capability NASA and its partners are looking to develop to enable human exploration of Mars is that of finding and accessing the water found in the Martian regolith. Along the way, they also want to better understand the subsurface of the Moon. The goal of the Moon and Mars Ice Prospecting Challenge is to ideate and test solutions to fulfill these needs. Hundreds of university students have been involved in solving this problem, providing NASA with valuable lessons learned through their research and testing.

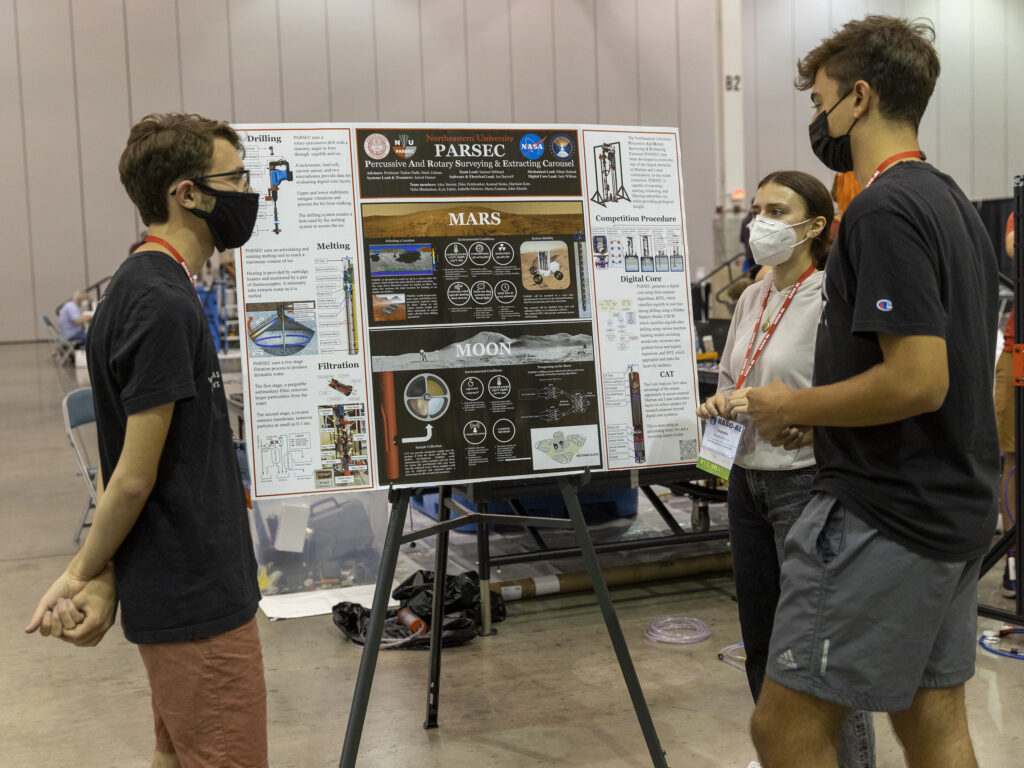

Planning a competition like this, however, is no small feat—enter SMAB engineer Chris Jones and Shelley Spears, the Director of Education and Outreach at the National Institute of Aerospace (NIA) and principal investigator for MMIP. Spears works very closely with NASA and industry experts to develop and execute the RASC-AL competition. She focuses on what the industry would find most helpful to advance the technology for harvesting ice to process into water on the Moon and Mars and translates that into a real competition. Jones serves as a member of the steering committee, which helps set the context of the challenge, reviews proposals submitted by the university teams, and selects the designs that seem most promising. During the competition, Jones also serves as a judge, evaluating the final papers and posters submitted by the teams alongside the hardware they designed.

“It takes a lot of different kinds of people on a team to come up with good solutions.”

Spears and Jones each have a unique history with the Moon and Mars Ice and Prospecting Challenge. They both got their start in the classic RASC-AL Classic competitions, with Spears having led the implementation of these competitions for over a decade. When planning began for Langley’s centennial celebration, center leadership expressed interest in creating a hands-on university competition at Langley to showcase the research being done at the center. Spears says they began “peeling the onion back” to determine what would be most useful to NASA and the space industry, as well as what would pose an interesting challenge for the competitors. It was initially assumed this competition would be “one-and done”, but afterwards, there was still significant interest from universities and within NASA to explore the concepts of harvesting ice and measuring subsurface characteristics using drilling telemetry. There were also still many approaches to be tested and lessons to be learned, so the competition became an annual event. Over the five years the competition ran, the university teams continued developing and testing unique approaches to the challenge.

Jones, on the other hand, started out as a competitor himself. In 2009, Jones competed as a student in RASC-AL Classic. The challenge: design a lunar base that could support twenty people on the Moon. The following year, Jones competed again on a different challenge. While his team didn’t win either time, Jones learned about both technical analysis and effective communication and earned a reputation as an enthusiastic competitor. Through the competition, he also got to know SMAB engineer Patrick Troutman, the NASA sponsor for the activity. Years later, after Jones joined SMAB, Troutman recommended that he take over administering the challenges. When the wheels began turning for the first iteration of the MMIP, Jones was on-hand with the relevant experience to help make it a successful competition.

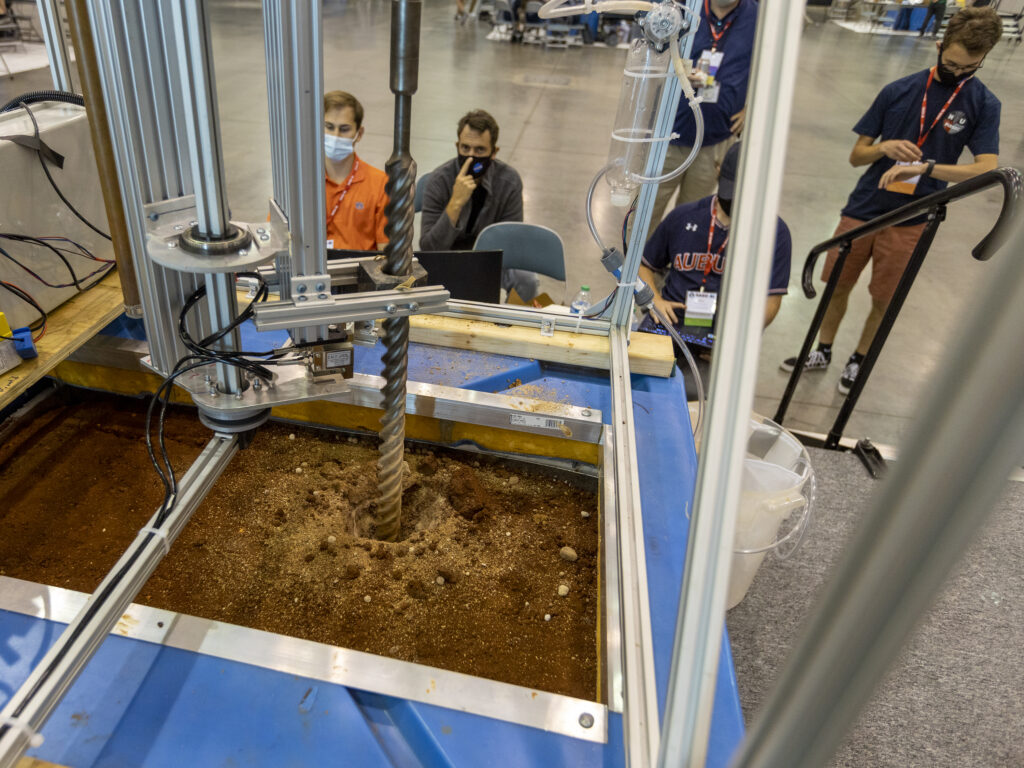

Since its conception, MMIP has been a labor of love, filled with days of hard work, triumphs, and low points. Spears recalls that the first year of the competition required a lot of elbow grease. One of the biggest challenges was designing a testbed that would best simulate drilling on the surface of Mars. She scouted gravel yards and supply stores, picking out bags of rocks and clay to find the right combination to mimic NASA’s current understanding of Martian regolith. Creating the ideal testbed also required keeping it cold. One of the team members, an educator-in-residence from Hampton City Schools, who also happened to be a fisherman, suggested looking into commercial fishing coolers. This idea ended up being the perfect solution, supporting the thousand pounds of ice and regolith simulant while maintaining its frozen state in the Virginia summer heat. Spears commented when planning a competition like this, “It takes a lot of different kinds of people on a team to come up with good solutions.”

“These are teams that are technically competing against each other, but they move past the competition to work together toward the bigger goal and the bigger mission.”

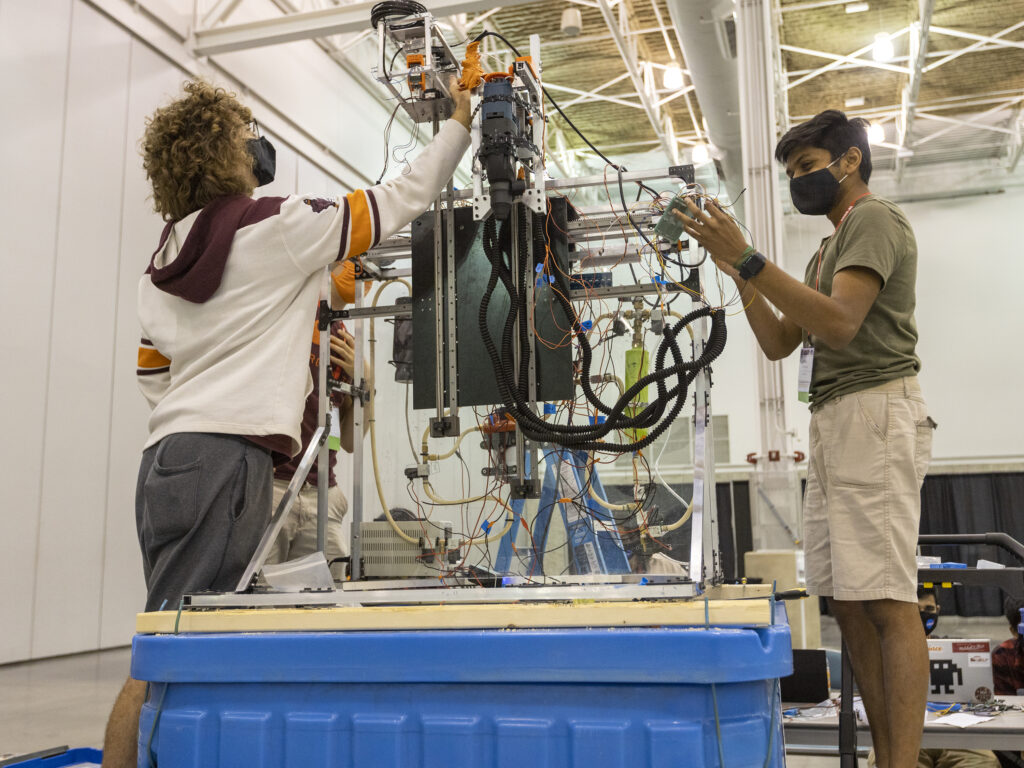

In 2020, the competition faced a unique challenge when the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Despite the circumstances, Spears and her team decided, “The world is not stopping because of the pandemic; we are not going to cancel.” Although the competition didn’t exist in its usual capacity, the show went on. While university teams throughout the country moved online, they continued to design and test their concepts. Students ran to labs to take home equipment hours before their labs shut down. Parts that were originally intended to be made in the schools’ machine shops were redesigned to be 3-D printed. The competition managed to go on in a strange virtual environment, with teams using collaborative capabilities to continue refining their designs. Some teams were able to test their systems on their campuses and send in videos of their demonstrations. For many of the teams, though, these concepts were the foundation that was passed on to the next year’s team when the competition returned to in-person demonstrations.

Sharing his favorite stories from competition day, Jones marvels at the camaraderie between the teams, despite the inherent competition between them. Without fail, every year, a team ran into difficulties and, without fail, other teams came together to collaborate and troubleshoot the issue. Jones recalls a team that had brought a 3-D printer to manufacture replacement parts. When a competing team had a part fail with no spare, the team who brought their 3-D printer offered to reproduce the part for the other team. Jones says, “These are teams that are technically competing against each other, but they move past the competition to work together toward the bigger goal and the bigger mission.”

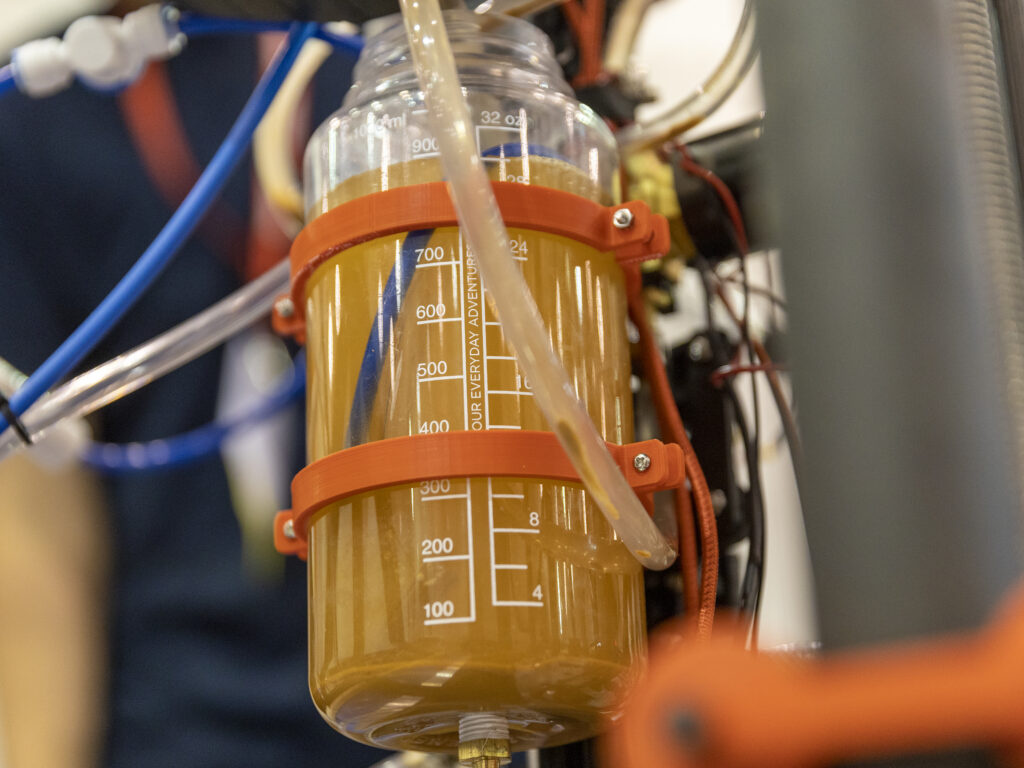

For Spears, the goosebump moments of the competition come when a team first harvests water. Spears says, “When a team actually harvests water, [we] see the eruption in the facility: huge smiles, big high fives. Could be a drop or two, but they are so excited.” The teams often overcame a lot of failure and frustration to get to that point, so when it happens, those are the most rewarding moments for everyone involved.

One of most important challenges to solve before establishing a sustained presence on Mars is that of acquiring water. Without water, human exploration is “dead in the water”, so-to-speak. Helping to solve that challenge is central to the RASC-AL Moon and Mars Ice and Prospecting Challenge. The competition inspires students to work with NASA and industry to develop novel and technologically sound ideas while NASA and industry partners see exciting concepts tested with hardware. In Jones’s words, “Everybody gets a benefit from doing [the competition]. As a result, we’re making progress toward the systems we’re going to need to keep venturing out into space, and we’re continuing to inspire and bring along the next generation of folks that are going to help us do it.”

2021 Moon to Mars Ice and Prospecting Challenge

Author: Samantha Vold; Contact: Chris Jones

Published: March 2022