Starting HAVOC for a Venus Exploration Concept, featuring Dale Arney and Chris Jones

What would it take to send humans to Venus? After a meeting discussing human Mars missions, Dale Arney and Chris Jones wondered what the differences would be in designing a crewed mission architecture for Venus. Armed with their space systems analysis skills and a healthy dose of curiosity, soon their High Altitude Venus Operational Concept (HAVOC) was born.

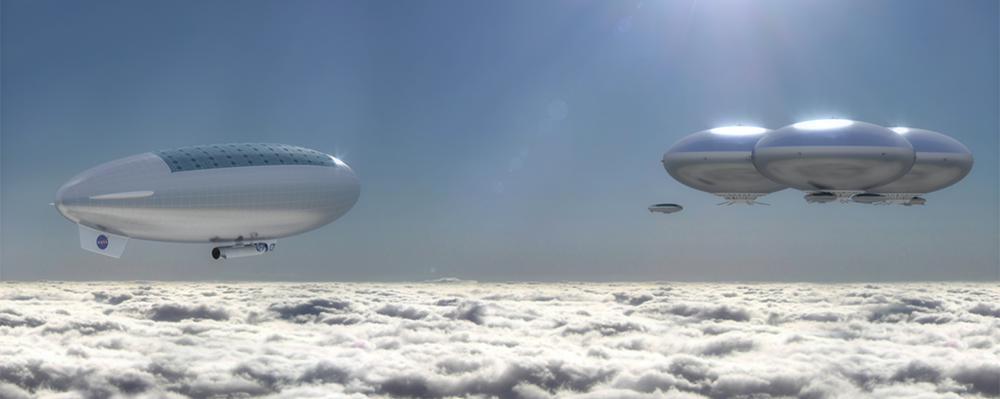

Arney and Jones, both aerospace engineers with NASA Langley’s Space Mission Analysis Branch (SMAB), developed their initial HAVOC plan and proposed further study. After being selected for internal project funding, they put together a team that included systems analysts, student interns, aircraft design engineers, trajectory analysts, and Entry, Descent, and Landing (EDL) experts to build the concept up from the initial idea. Although there were many similarities to Mars exploration plans, such as starting with robotic exploration before sending crew, the Venusian environment presented its own set of unique challenges. With Venus’ inhospitable surface conditions of melting temperatures and crushing pressures, the team looked for other destinations for the crew. About 50 km (~30 mi.) above the surface of Venus, the environment changes to the most Earth surface-like conditions within the Solar System, suitable for supporting airships. Although the temperature and pressure concerns were mitigated at that altitude, another challenge appeared: the presence of sulfuric acid clouds, which are highly corrosive. This meant that the team brought in even more experts from across NASA Langley to brainstorm and test ideas for materials that could resist the acidic environment while enabling solar power for the HAVOC airships.

Although HAVOC was intended as an internal study to develop analysis skills and test tools and capabilities, it provided much more. Arney and Jones were both fairly new to SMAB, so the project gave them the opportunity to work through the integrated process of designing a NASA mission concept for human exploration and leading a multidisciplinary team. As their backgrounds were both in engineering, this was also their first time working with planetary scientists to determine which science investigations were of the most interest and how the expected Venusian environmental conditions would impact the design. In doing so, they integrated scientific considerations with the engineering and human factors for both the vehicle and the overall campaign concept.

“NASA is, and should always be, the tip of the spear when it comes to space exploration and doing ambitious things in space. If we aren’t consistently looking beyond the horizon, we’re not doing our job.”

As Arney and Jones published their work on HAVOC through technical papers, an interview with an engineering society, and an accompanying video that illustrated the concept, the media and general public became fascinated with the idea. They participated in frequent interviews for news articles and the video went viral, with over one million views. In Jones’ perspective, “[HAVOC] was an idea that was really underexplored. By going through and figuring out the technical analysis and telling a compelling story, we were able to capture the imagination of the public and the scientific community. It was a really impressive thing to see how diving into a novel project can spin off into major positive impacts for all involved and how having an idea can have a much larger impact… People get excited when NASA wants to do something new and cool in space. People still get really excited about what NASA is doing.”

Just as HAVOC inspired the general public, NASA also sparked Jones’ interest in space exploration. Growing up, he visited NASA’s Kennedy Space Center often, and watching Star Trek made him wonder about how space could play a role in everyday life. After studying mechanical engineering for his undergraduate degree, Jones continued on to graduate school for aerospace engineering, working closely with SMAB through his PhD program at the local National Institute of Aerospace, where Arney was also completing his PhD in space systems architecting. This allowed the two to work together while they were both still doctoral students. This focus on systems analysis allowed them to see how all the pieces of a mission architecture fit together and work on refining the concept in more detail, including identifying what technologies were necessary to advance these concepts to reality. Arney and Jones’ shared background and training led them to have complementary skills in technology assessments and space mission design, preparing them for their jobs in SMAB and their successful work on HAVOC.

If HAVOC was not meant to be NASA’s true mission for human exploration of Venus, what was its value? Arney summarizes, “Looking at what technologies need to be developed [for HAVOC] is also applicable to other missions for the Moon, Mars, and beyond. All this work is interrelated, and our ability to do things in space advances.” The HAVOC study serves as one potential idea of how NASA could explore the Solar System; therefore, it can help inform the next round of studies and concepts and provide insight into what may be possible. Expanding to a broader view beyond HAVOC’s impact, Arney asserts, “NASA is, and should always be, the tip of the spear when it comes to space exploration and doing ambitious things in space. If we aren’t consistently looking beyond the horizon, we’re not doing our job. We need to be developing the advanced technologies, the operational capabilities, such that it pushes us one step closer to being a space-faring civilization so that operations in space are fairly routine and commonplace. All of those things don’t happen if we aren’t pushing the boundary… NASA should be the one out in front doing the hard things that we can’t envision.”

Author/Contact: Emily Judd

Published: March 2022