How History May Inform Our Future on Venus, featuring Jannuel Cabrera

The Moon and Mars are not the only celestial bodies NASA is planning to visit again.

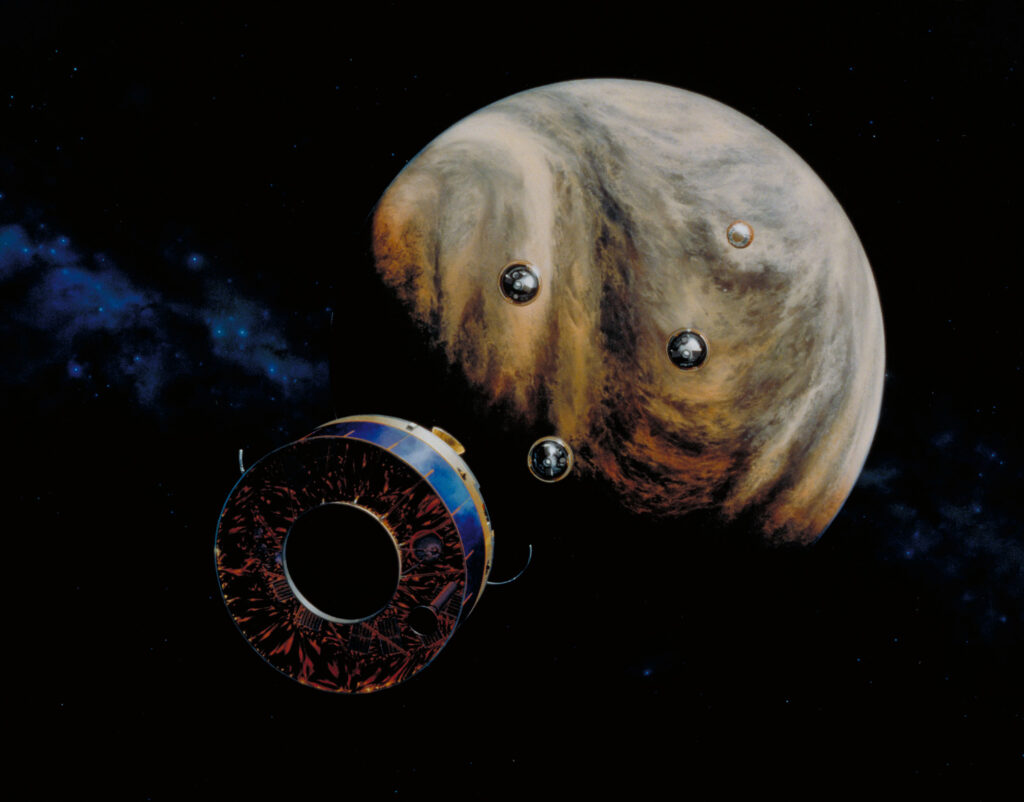

In the 1970s, NASA sent uncrewed spacecraft to Venus for the first time to observe the planet’s atmosphere and surface. As part of the Pioneer Venus project, four probes descended into the Venusian atmosphere in late 1978, each essentially doing the same work, but there was one crucial feature unique to every one of the four.

“Where they differed was the way that they entered the atmosphere,” explains Jannuel Cabrera, an aerospace engineer for the Vehicle Analysis Branch (VAB), part of the Systems Analysis and Concepts Directorate, at the NASA Langley Research Center (LaRC) in Hampton, Va.

“Some of them entered the atmosphere quite steeply. They each had a different trajectory from one another, so as each entered in a shallower angle, it could take a different kind of measurement.”

The probes transmitted data throughout their descent to the surface. Two of them actually survived impact with the planet’s surface, with one continuing to send information for more than an hour. Cabrera is focused on those historical measurements to inform the future of Venus exploration.

For someone who loves both history and space, it’s a perfect gig, and one carrying a responsibility that the young engineer does not take lightly.“If you’re exercising good engineering judgment,” he asserts, “you are leveraging a past knowledge base effectively and relying on the expertise of folks who know more than you.”

Stargazing as a Child

Cabrera’s fascination with celestial bodies started very early in life, with his family in the Philippines. He remembers his uncle was an avid stargazer who would go outside every night after dinner.

I would follow him out there and ask, ‘What’s that? What’s that? ‘And he would point out all the cool constellations, like Cassiopeia and Pleiades, which the latter is, incidentally, the supercomputer out at Ames,” he says. “So, when I interned at Ames Research Center and made that connection, I was like, ‘Oh, my gosh, you know, I saw that when I was a kid!’”

Before that first internship with NASA, though, Cabrera confesses that he wasn’t quite sure where his career path would lead him. He and his family emigrated from the Philippines while he was a child, so he was focused on assimilating into a new culture and country. Math, calculus and physics captured his interest in high school, and he discovered a talent for those disciplines.

And then, one day, he was looking up.

“I saw a plane in the sky,” he says. “And I thought, ‘That’d be kind of cool. I’ll do aerospace engineering as an undergrad!’”

“My mentor made sure that I had the tools I needed and the knowledge that I needed to succeed. He always tells me, ‘If you can do better, do better.’ That’s kind of become my mantra.“

The Path Becomes Clear

While earning his undergraduate degree at New York’s Syracuse University, Cabrera gravitated towards aerodynamics. Ultimately, this led to his earning post-graduate degrees from Purdue University.

The first Ames internship focused on space traffic management, the study of how to keep all those satellites circling overhead from running into one another.

“I think it was one of those things where I had really started liking research and discovering new knowledge,” he explains. “I thought it would be a great way to gain experience and just working in a nonacademic setting because up to that point, all that I ever knew was just classes and academia.”

His second internship involved running aerodynamic calculations on Pterodactyl, a project that looked at different ways to manage the flight path of a vehicle entering a planet’s atmosphere.

“In that experience,” he recalls, “I learned what it felt like to love what you were doing, and I knew it was the kind of work that I wanted to break into.”

So when a Pathways internship in aerodynamics and aerothermodynamics opened within the Vehicle Analysis Branch (VAB), Cabrera leapt at the chance.

Fast forward two years: Cabrera now specializes in aerodynamics and aerothermodynamics analysis for VAB.

He’s quick to credit his mentors for guiding him along his path with NASA, especially Tom West, also in VAB.

“Tom made sure that I had the tools I needed and the knowledge that I needed to succeed in what I’m doing right now. He always tells me, ‘If you can do better, do better.’ That’s kind of become my mantra.”

Next Stop: Venus

Cabrera’s current work could be crucial as NASA plans to return to Venus via Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble-gases, Chemistry and Imaging (DAVINCI) a flying analytical chemistry laboratory that will study the planet using both spacecraft flybys and a descent probe. DAVINCI is tentatively scheduled to launch June 2029 and enter the Venusian atmosphere in June 2031.

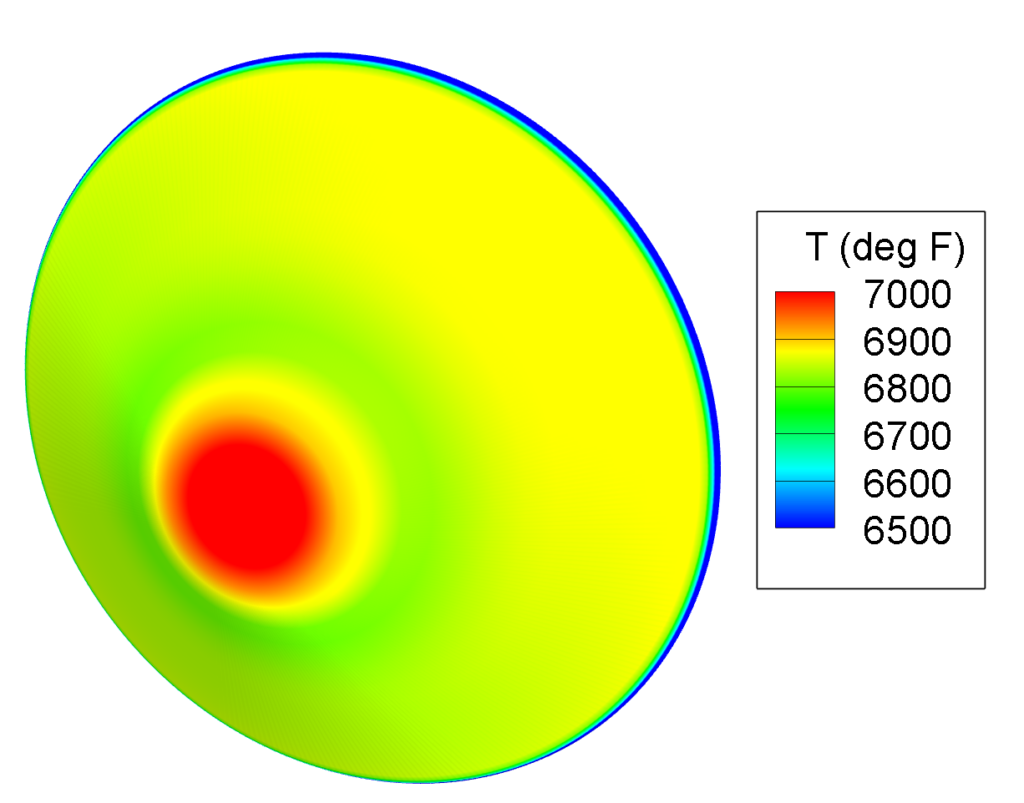

“In the ‘70s, we had these methods to calculate the expected amount of heating around the probes when they were entering the atmosphere. You want to calculate how hot they get so that you can protect them properly.”

Twentieth century engineers were limited by computational power, so they relied heavily on more simplified, physical modeling and methodologies. Now Cabrera uses new and improved versions of both, along with the historical data from the Pioneer probes and more powerful computers to model possible phenomena. Ultimately, all this analysis will help build a vehicle that could approach and land on Venus safely.

“I’m interested in how hot that thing would get,” he says. “How can we design it really well so that it doesn’t melt or get destroyed as it’s screaming through the atmosphere so that my planetary scientist friends can do their measurements to the best of their abilities?”

Cabrera’s work could also prove useful as a model for studying the temperatures that vehicles must survive when entering atmospheres of other planets.

“While not everything we’ve done to model the Venus environment will directly translate to, say, a Neptune probe, the underlying processes we established should still be looked at in order to come up with the best practices that would be most appropriate for Neptune.”

Further exploration

- Venus Resources

- Pioneer Venus 2

- The Pioneer Venus Orbiter: 11 Years of Data

- 40 Years Ago: Pioneer Orbiter Begins Most Comprehensive Study of Venus

- NASA’s New Mission to Venus: DAVINCI+

On Cabrera’s Sci Fi Shelf

The Three-body Problem (first novel in the Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy), by Cixin Liu

“It’s a reimagining of the Cultural Revolution in 1960s China. And for someone who’s really into world history, that was what hooked me. Not really the aliens coming to Earth type of type of angle. It’s reimagined in such a way I thought was fascinating. I appreciate history, especially when it comes to other empires or just other cultures.”

Author: Sondra Woodward

Published: March 2023